Getting the Hang of Using the Ladder of Inference

Data analysis is a cornerstone of effective business leadership. But it’s also a process prone to missteps. In the rush to make decisions, leaders may jump to conclusions before fully understanding what the data says.

“Our brains are programmed to take shortcuts to accelerate decision-making,” says Harvard Business School Professor Amy Edmondson, faculty chair of the Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB) program, who teaches the online course Dynamic Teaming. Even though we may be aware that jumping to conclusions is not the most effective way to make a decision, it is not helpful to tell others not to. Rapid conclusions are frequently reached without conscious awareness. The ladder of inference is a cognitive tool that Edmondson suggests using to reduce the likelihood of making snap judgments.

What Is the Ladder of Inference?

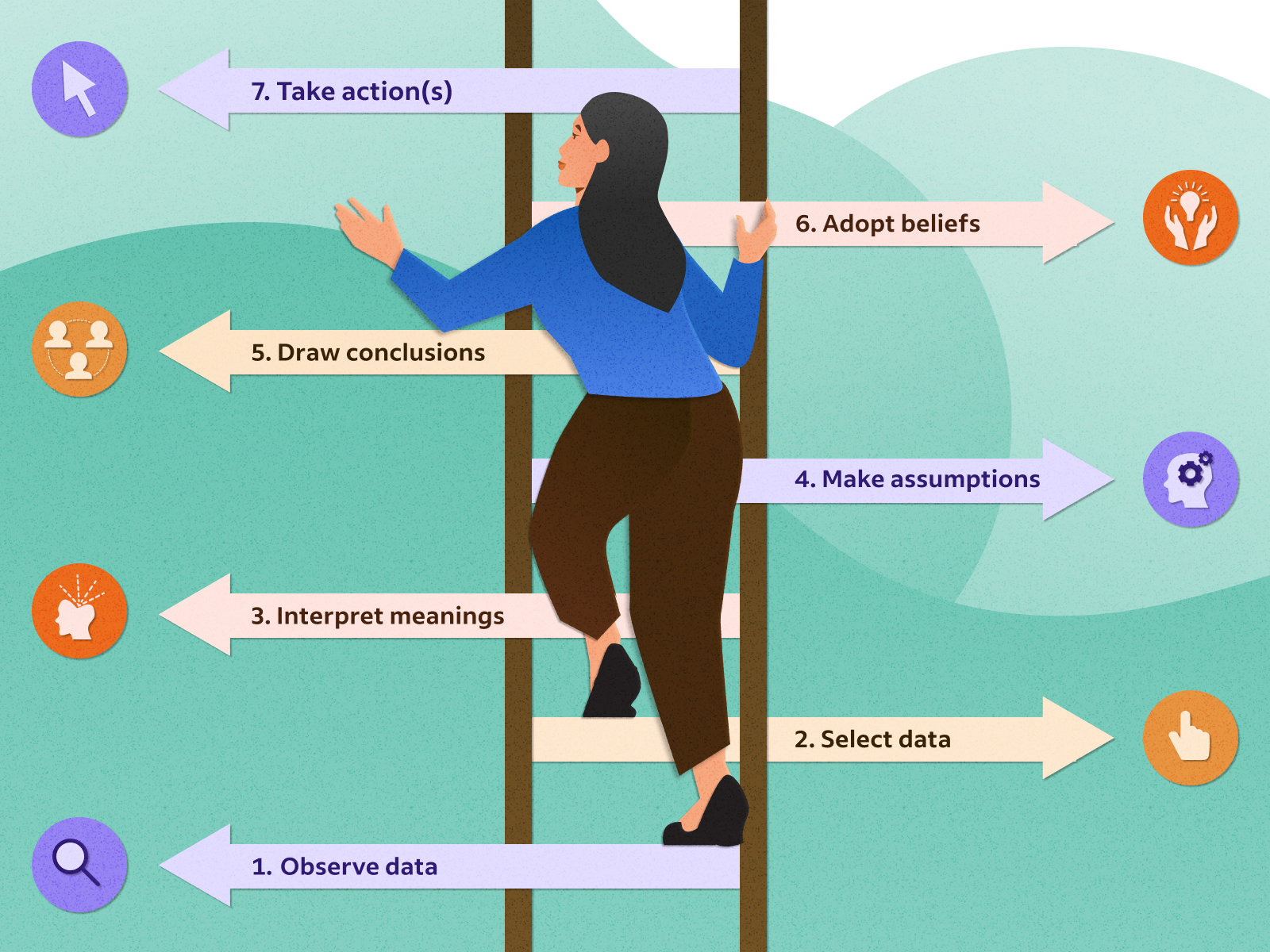

Chris Argyris and Donald Schön, two organizational behavioralists, created the ladder of inference as a way to map how people make decisions. In Dynamic Teaming, Edmondson states, “As leaders, we need to step back and analyze assumptions, biases, and judgments to understand how we arrived at our conclusions and to look for gaps in our thinking.” If you find yourself jumping to conclusions without fully considering the facts, the ladder of inference can help you reflect on your thought processes and avoid the negative consequences of rash decision-making. The steps, as described by Edmondson in Dynamic Teaming, are as follows:

Climbing the Rungs of the Ladder of Inference

The ladder of inference is a mental model that shows how the brain makes decisions quickly, though not always effectively. Understanding the ladder’s rungs can help you recognize why you make certain choices and spot gaps in your reasoning.

Step 1: The Data Pool Your pool of data

All of the situation-relevant raw information—is at the base of the ladder of inference. This includes formal business metrics, institutional knowledge, and personal observations informed by your beliefs, values, and expertise. When faced with a problem, your mind instinctively searches this pool for familiar patterns.

Step 2: Select Your Data

The first rung represents the initial filtering of information. Since it’s impossible to process everything, the brain instinctively selects certain data and ignores the rest, often without conscious awareness. Recognizing this subconscious choice is key to understanding how biases can shape your thinking from the start.

Step 3: Interpret Your Data

The second rung is where your brain interprets the selected data and assigns it meaning. This step is critical; it shapes your understanding of the situation. However, if the data is incomplete or colored by past assumptions, your interpretation may be misleading.

Step 4: Reach Conclusions

After interpreting the data, your brain quickly draws conclusions about what it all means. These judgments often feel intuitive but are frequently based on personal biases and past experiences rather than objective evidence. While essential for decision-making, this step can lead to flawed reasoning if not examined critically.

When You Reach the Top: Take Action

Once your brain forms a conclusion, it begins to influence your actions. This is where internal reasoning—often invisible and automatic—translates into real-world behavior. Your actions are shaped by the conclusions you reached as you climbed the ladder of inference, whether you’re sending an email, making a business decision, or just changing your tone of voice in a conversation. The risk is that climbing the ladder too quickly or relying on incomplete or biased information can lead to misguided actions. That’s why it’s so important to pause at the top. Before you act, as Dynamic Teaming suggests, take a step back and ask yourself: You can put your thinking to the test, spot potential understanding gaps, and make necessary adjustments by purposefully working your way back down the ladder. In doing so, you make better decisions and exhibit more thoughtful, intentional leadership.

The Ladder of Inference in Practice

Edmondson suggests pausing to explain your conclusion and going backwards down the ladder to examine your reasoning if you find yourself jumping to conclusions. Identify the data you focused on, how you interpreted it, and what assumptions may need to be challenged, or supported, with additional information.

For example, imagine you run a coffee shop and are reviewing usage data:

You notice that the consumption of oat milk has increased recently. You immediately associate the spike with a past instance when increased usage was caused by staff doubling up on paper cups.

Based on that pattern, you conclude that baristas are likely overpouring oat milk.

At this point, you might feel tempted to act, perhaps by emailing your team about being stricter with their oat milk usage. But if you pause and apply the ladder of inference, you may realize a recent event influenced your interpretation and that the data you evaluated was incomplete.

You find out after doing more research that there has been an increase in orders for oat milk latte since a new gym opened nearby. By taking time to assess your initial data critically, you realize your team wasn’t being wasteful; demand had simply increased. With this knowledge, you might decide to take a different route, like selling more drinks made with oat milk or finding a bulk supplier to meet growing demand.

Collaborate with the Dueling Ladder of Inference

The ladder of inference is a powerful tool for individual reflection and can be just as effective in bringing clarity to group decision-making. When working in a team, it’s common for members to focus on different data, leading them to reach differing conclusions and propose varying courses of action. “Dueling ladders of inference” are Edmondson’s term for this. Edmondson uses the analogy of two people sailing in the same boat. “Past experiences may lead us to focus on different facets of the available information,” Edmondson says in Dynamic Teaming. For instance, I might have focused on the gray clouds because I was worried about the weather. You may have hit rocks before and want to prevent it from happening again. We each turn what we notice into our own version of what’s going on.”

To help navigate opposing viewpoints, Edmondson recommends a two-step analysis of advocacy and inquiry, as outlined in Dynamic Teaming.

This method works as follows:

Advocate for your own views thoughtfully: Clearly share your conclusions, explain the reasoning, and support your opinions with relevant examples.

Inquire to understand others’ perspectives: Ask team members to share their conclusions, views, reasoning, and examples—just as you did—so you can better understand how they arrived at their point of view.

The dueling ladders of inference must be analyzed by the team in good faith, with the goal of understanding each other’s perspectives rather than immediately attempting to disprove them. By thoughtfully examining how each person arrived at their conclusion, the team is better positioned to align around a well-informed, shared course of action.

Make Wiser Decisions with the Ladder of Inference

The ladder of inference empowers you to make more thoughtful decisions by mapping the mental steps you take between observation and action. Instead of reacting on autopilot, it encourages you to pause, examine your assumptions, and trace your reasoning back to the facts. This practice not only sharpens your judgment—it also strengthens communication and reduces conflict within teams. By regularly utilizing the ladder framework, you can approach complex situations with greater clarity, understanding, and confidence.

To further enhance your decision-making, consider taking an online course like Dynamic Teaming. With interactive learning modules and case studies from global industry leaders, the course offers practical and actionable insights and tools. Throughout the course, you’ll discover innovative strategies developed by HBS professors to boost your leadership skills and improve performance within your organization and beyond.